On Becoming an NYC Nurse

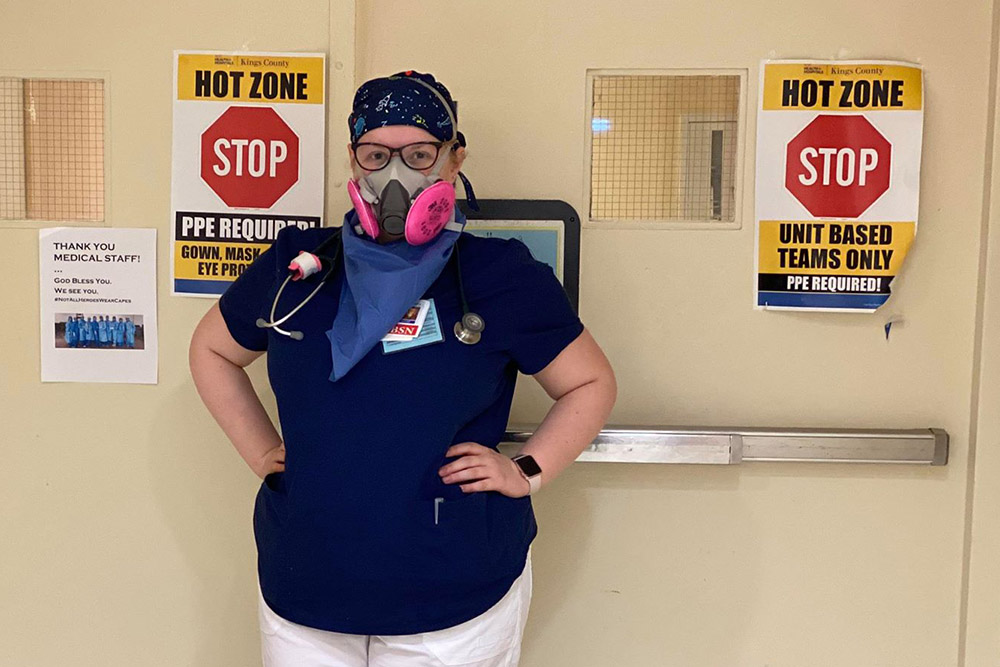

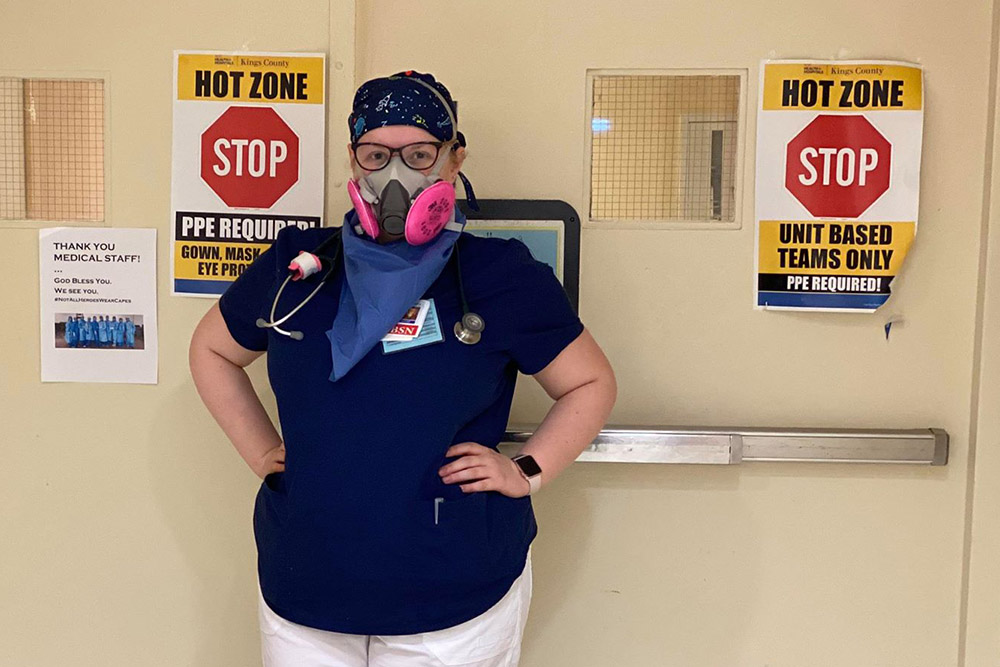

Of all the roads she’s traveled, alumna Heather Lister had pain as her near-constant companion. It made her the perfect COVID nurse.

Lister, a native of Culpeper, Va., signed up to become a travel nurse just as COVID crept in from opposite coasts in the United States. Watching the pandemic unfold from her home in Charlottesville, and inspired by New Yorkers’ resilience, she signed up to be a travel nurse, leaving her job in hospice care for work at the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic in Brooklyn, NY.

That her pain abated at the moment the novel coronavirus struck makes Lister, just 26, smile at the irony, and not for the first time. Dogged by pain much of her adult life, there were moments over the last eight years when she worried her health would snuff out her nursing career, and take away all she’d worked for. But dealing with her own suffering has drilled deep her reservoir of empathy, and given her a foundation of strength to boot, she says. COVID provided the occasion to help.

“I’m not really a leaper,” laughs Lister, “but I can empathize with people because I’ve gone through a lot. I’ve always been about an hour away from home, and this is a time when I’m more needed than ever. So why not go and help?”

Without surgery last fall to relieve symptoms of complex regional pain syndrome, the journey would have been impossible. The procedure implanted an electrode in her spine powered by a rechargeable battery nestled in her flank that sends weak pulses to block pain signals. It means she can walk without a cane. Doesn’t rely on pain medication. It means her migraines have lessened, she’s lost weight, and feels more clear-headed than she has in years.

“I felt like I was soaring,” said Lister, 26, of the period immediately after the surgery, “and in the prime of my life. I have so much energy. I’m a completely different person, and for the better.”

It also meant she had the strength to be a frontline nurse. And so on April 5, she packed up her Chevy Equinox and hit the road for New York City and the community hospital where she’d been assigned.

From her rented apartment, it’s a 15-minute drive to the public hospital where every patient she has suffers from the lung-, kidney, and breath-ravaging virus. Pre-pandemic, the hospital had 40 ICU beds; by early April, when Lister arrived, the number of intensive care patients had swelled to 200.

Many of Lister’s patients are immigrants from Jamaica, Trinidad, Cuba, or Haiti. Most have comorbidities, such as heart disease or diabetes. Most cannot self-regulate their body temperature, and require heating or cooling blankets. Some lie on their stomachs; others cannot tolerate the position. Every one of them is intubated and has a catheter. Many require continuous dialysis, have multiple peripheral lines, and lie in beds surrounded by “machine after machine.”

Lister, who works as many as five 12-hour shifts each week, cares for patients and explains to families what’s happening, trying to assuage the deep fear many have of hospitals. Many of her COVID patients in the hospital’s “hot zone” arrived too late. Some received home remedies that further complicate their care.

As she speaks with stricken family members, Lister draws from her background in hospice as death remains a regular visitor. But inner resilience has kept her both afloat and humble. She plans to remain in Brooklyn permanently, and find a job once the pandemic is past, and waves off the word hero.

“I would’ve stayed and helped Virginia,” she adds, “but New York needed me more.”

###