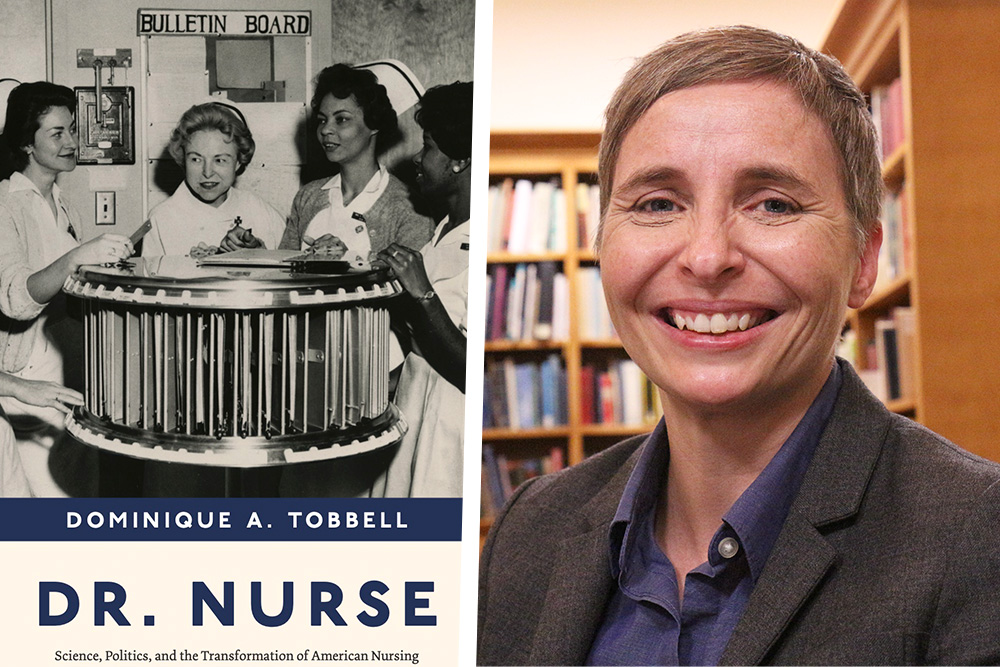

On DR. NURSE

A conversation with healthcare historian Dominique Tobbell, Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry director and the Centennial Distinguished Professor

What motivated you to tackle this subject in a book?

While I was doing my graduate work at University of Pennsylvania, I remember my dissertation advisor telling me, “You have to pay attention to nurses to truly understand the history of health care.” After I got to my first teaching job at the University of Minnesota, I started interviewing nurses who’d trained in the 1940s and 1950s when major changes were taking place in health care, and thought, “Absolutely.”

They’re the largest segment of the health care workforce and spend way more time with patients than any other group. Nurses are so important.

Explain the title, please.

On the one hand, the book is about the history of the doctoral preparation of nurses. But it’s also about recognizing the controversy over titling and scope of practice and how up in arms physicians have been historically about nurses claiming this space. Physicians fought really hard against and have been quite vitriolic in their opposition to nurses earning the title of “doctor” . . . when the DNP was introduced in the 2000s, for instance, organized medicine, including the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Medical Association, even created a marketing campaign emphasizing who, exactly, should be called doctor—and it wasn’t a nurse. There’s been real gatekeeping around the title of doctor, so the book’s title is a nod to that.

"It was a pivotal moment: the Equal Rights Amendment had failed to pass, and the American Nurses Association convention wouldn’t take it on ... and a new group of nurses wanted to do something different, something inherently feminist. Using ethnography and other qualitative research methods, they started asking, 'What does health and healthcare look like from a woman-centered perspective? How can we advocate for the feminist framework in the science that we do?'"

Dominique Tobbell, Bjoring Center director and author of the book DR. NURSE

Some of the early healthcare silos were meant to be broken down in the 1940s with the development of academic health centers (AHCs). Talk about AHCs’ origins and development.

The arguments that were made about why AHCs needed to be created—for greater administrative equality and coordination between the different health science schools and teaching hospitals—were great in theory. But interprofessional education, research, and practice in healthcare has been a goal since the 1940s; and since then, it’s really struggled to come to fruition. So yes, you can say you’re dismantling silos, but often you’re not.

- read ON MY BOOKSHELF (VNL spring/summer 2021)

You have generations of folks for whom that’s not been their approach. Particularly in the 1950s, to the 80s, 90s, and later, gender, sexism, and the privileged status physicians occupied came under scrutiny, but there was still a prevailing belief that physicians are captains of the team: and that doesn’t set up a fruitful, interprofessional dynamic. And barriers aren’t just about people but about institutions. Medical schools were able to secure significant research funding and generate substantial clinical revenue, which meant that the political and economic interests of medical schools tended to dominate within AHCs

Even when there’s a concerted effort to break down silos, it’s difficult. For example, at the University of Florida in the late 1950s and 1960s, there was a team of deans of nursing, medicine, and pharmacy, and provost who were committed to schooling health professions students together. But it brought up real problems. Curricula were tight; no one wanted to give up space. And nursing and medical students were at different academic levels and ages: while nursing students were undergraduates, medical students were post-graduate students.

At schools attempting interprofessional education at the bedside, it tended to depend on personalities: were physicians really willing to give up their power and authority over the nurses? Interdisciplinary research teams that included nurse scientists also struggled to be taken seriously, particularly in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, because nursing science was such a new discipline. Some of the barriers are deeply ingrained: sexism, administrative and financial issues, institutional politics.

Nursing has historically been the domain of women. Is it inherently feminist?

Nursing has had a complex relationship with feminism. During the 1960s and 70s, for example, many feminists called on women to reject careers in nursing in favor of careers in medicine. Nursing was held up as women’s subordination, not a feminist pursuit. For these feminists, “If you go into nursing, you’re reinforcing the patriarchy; not advocating for women’s causes. If you’re smart, go into medicine.”

In the late 1970s and 80s, feminist scholars critiqued science, arguing that its symbols, rhetoric, the way certain research methods were valued, and particularly, notions of objectivity were distinctly masculine ways of relating to the world. They observed that women scientists tended to cluster in disciplines that were considered less “objective,” including the behavioral and social sciences where qualitative research methods were often used. These disciplines, not coincidentally, also had less prestige and less research money.

During these years, some feminists advocated for a different type of science, one underpinned by women’s supposedly distinctive “ways of knowing”—including caring, holism, and an emphasis on the environment—and using distinctive research methods, such as ethnography: a lot of work that sounded exactly like what nurse scientists were doing. But these same feminist scholars denigrated that nursing link, seeing nurses only as subordinate to physicians, and not engaged in the work of scientific knowledge production.

There was, however, a small group of feminist nurses, led by Peggy Chinn and Charlene Wheeler, who organized in the 1970s and 80s and advocated that nurses do their science differently. It was a pivotal moment: the Equal Rights Amendment had failed to pass, and the American Nurses Association convention wouldn’t take it on. Rather than trying to do “normal” science, this group called on nurses to do something new and different and what they saw as inherently feminist. Using ethnography and other qualitative research methods, they started asking questions like, What does health and healthcare look like from a woman-centered perspective? How can we advocate for the feminist framework in the science that we do?

It’s kind of strange that a field like nursing—focused on health, holism, and the impact of the environment—did not make room for study of patients of color or include nurses of color across much of its history.

Right—nurses created the discipline of nursing science in the context of heavily segregated education and healthcare systems. Black women, in particular, but also other women of color, faced systemic barriers to pursuing nursing education. (At this time, men, regardless of race, also faced barriers accessing education and careers in nursing). When Black women could get access, it was often at the lower educational levels, like the LPN program at UVA or in associate degree programs. Limiting who gets access to the higher academic levels, particularly doctoral education, shapes the identity of a discipline and informs the research questions that a discipline values and prioritizes.

- read CELEBRATING BLACK NURSE LEADERS IN THE FIGHT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS AND HEALTH JUSTICE (a Bjoring Center FlashbackFriday)

Early nurse scientists were primarily focused on questions like, How do we make our science visible? How do we get research funding? How do we get taken seriously by our colleagues in the biomedical sciences? Their experiences as (mostly) white women shaped what they studied and were interested in, and, because they typically didn’t ask questions about the health needs of people of color, or about the effects of racism or poverty on health and health outcomes, those disparities became even more deeply reinforced.

While we need to be critical of this, it was certainly a broader problem of health science research at the time: the NIH and other major funding agencies were not interested in supporting research that addressed the social and cultural factors that impacted health and illness in low-income communities and communities of color. A problem that continues today is that it was much harder to get community health research funded than it was to get biomedical research funded.

People are products of their time, and they make choices. Nurses at the time had the choice to say, as they’re doing more now, “No, we’re going to prioritize research into the effects of racism and poverty on health because that’s a value we hold true.” But at the time they really didn’t.

"People are products of their time, and they make choices. Nurses at the time had the choice to say, as they’re doing more now, 'No, we’re going to prioritize research into the effects of racism and poverty on health because that’s a value we hold true.' But at the time they really didn’t."

Dominique Tobbell, Bjoring Center director, a medical historian and author of the 2023 book, DR. NURSE

In its annual rankings, U.S. News and World Report gives “points” to nursing schools who have faculty that both teach and have active clinical practices. But doing both seems difficult.

This is an issue beyond nursing. Health professions disciplines broadly speaking struggle with who’s going to do the teaching and who’s going to be engaged in clinical practice. And also, who’s going to do research to contribute to the advancement of clinical practice. Part of this comes out of the post-WWII university. Before the war, everyone was a teacher, but after, particularly at self-identified research universities, faculty were increasingly evaluated for their ability to secure research money and generate patents and publications. There was the belief that research and teaching can reinforce one another, and that in the practice disciplines like nursing and medicine, that being clinically engaged would benefit research and teaching, and vice versa. But you’re asking a single person to do research, teaching, and clinical practice. That’s a lot. How do you do that?

So it’s become a capacity issue. And in a research university where the ability of a department or school to secure research money, publish, generate patents, collaborate with industry, conveys status and, with it, institutional power, the institutional values attached to research, teaching, and practice shifts.

Clinical practice adds additional complexity. When nursing education moved into the university after the war, education and practice were, for the first time in nursing’s history, separated. Nursing faculty rarely held clinical appointments in the teaching hospital’s nursing service. And for some educators, a strict separation between education and practice was seen as essential to establishing nursing as an academic discipline. In other words, nursing faculty were discouraged from being clinically active. In the 1960s, some nurse leaders saw the costs of this approach and worked to “re-unify” education and service. But in addition to the capacity issue, they faced significant institutional and political barriers.

At medical schools, medical faculty who are clinically engaged can also generate a lot of clinical revenue through reimbursement, and Medicare subsidizes the costs of graduate medical education. But nursing has struggled to generate revenue from clinical practices because, since WWII, nurses have been salaried; their services aren’t specifically billed for. So, because the cost for nursing service doesn’t show up on the bill, no one sees its economic value, and hospitals aren’t reimbursed for their services. It becomes unappreciated.

Without a mechanism of generating clinical income, such as direct reimbursement, it has been difficult for nursing schools to justify, let alone prioritize, clinical practice, even as nurse leaders recognize the benefits of having a clinical engaged faculty.

"There was the belief that research and teaching could reinforce one another, and that in the practice disciplines, like nursing and medicine, that being clinically engaged would benefit research and teaching, and vice versa. But you’re asking a single person to do research, teaching, and clinical practice. That’s a lot. How do you do that?"

Dominique Tobbell, Bjoring Center director and author of DR. NURSE

How do you hope the book will be used?

I’d like the book to be useful to nursing as it moves forward—as a way to explain why nursing, and nursing science, came to be the way it is, the challenges it has, the choices that were made in the process, and the broader political structure that shapes nurses and their work.

It’s neat for me to be working with colleagues now who are doing the science, and working as nurses, to see how far nursing has come but also what it still struggles with. The concerns that nursing faculty and nurse scientists have today—of balancing the tripartite mission of education, research, and service; of nurse scientists having their research valued and visible within the university and health system; of having a seat at the decision-making table—are all issues that nursing has worked to navigate since the 1960s.

Understanding the history is important for how the profession and discipline moves forward. This is especially so as nursing and the other health professions are called to reckon with the racism embedded in the health care system and the racial inequities created by it. Understanding how nursing chose to construct its discipline, determined which knowledge and, thus, which type of research had value, and who would be valued as nurses and nurse scientists, makes clear that the choices made by nurses in the past—as do their choices in the present—has profound implications not only for who gets to work as a nurse, but also for who has access to healthcare and how those with access experience the care they receive.