Essay: 53 & Me

What in the world was I thinking?” I thought as I fumbled my phone-to-laptop connection like the middle-aged student I am.

Along with class registration, Zoom protocols, and learning to peruse virtual library stacks, everything about this go-around with graduate school—and I mean everything—had changed.

A school nurse with a master’s degree in psychiatric nursing, I’d enrolled in UVA’s Doctor of Nursing Practice program to better position myself to help address the nation’s escalating teen mental health crisis. Twenty-seven years had passed since I was last a student. I was now 53. I felt even older.

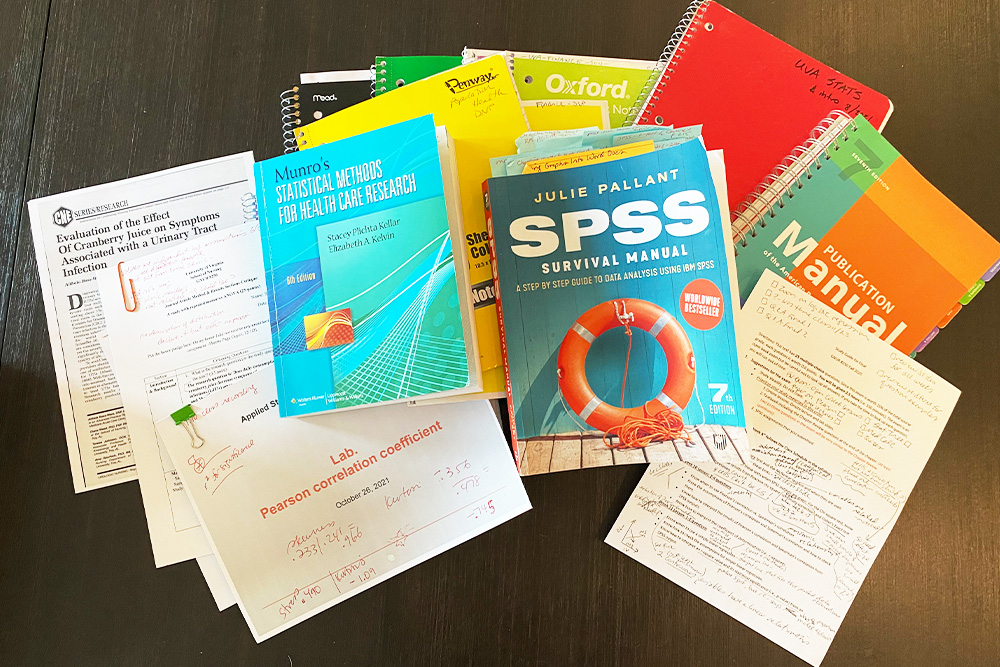

In the early 1990s, graduate school was a full-time affair providing instant camaraderie. Class involved paper-and-pencil notetaking, legions of spiral binders, and lively discussions that spilled over into lunches and afternoon coffee paid for with change people no longer carry. We’d brainstorm community care delivery models and how to help people struggling with addiction and mental illness, long before the opioid crisis brought seismic shifts in the early 2000s. In the afternoons, I’d cherish the peace of the library, and the warmth and concentration its piped-in air provided.

Back then, writing a paper required fancy legwork to find supporting literature. Academic journals, often deep in the bowels of the library, were organized in rainbow rows on shelves, each publication bound in a specific color. If the wanted volume was missing, an interlibrary loan could take weeks, which made hunting for and actually finding a journal article you sought thrilling. Making copies to be used later for quotes in your papers meant spending hours with the photocopier. I remember those idle, in-between-times with fondness, the Xerox hum my only distraction. I still miss gliding down the library basement’s organized stacks of rainbow rows.

Grad school in 2023 means I often don’t even have to leave home to complete assignments. Easily findable sources and APA formatted citations can be done with a click. And although this ease feels like magic, it’s still in-person classes I look forward to the most.

Early on in my first semester, we lingered over free food after statistics class, trying to figure out who was who (food being the one sure way to organize DNP students). “You’re the one who writes everything down in spiral notebooks!” my classmate proclaimed, not unkindly, but making me inwardly sigh and think, for the millionth time, that I was too old to be doing this. Especially statistics.

I’d survived childhood bullies and peer pressure, college, grad school, marriage, childrearing, a robust professional life, and even divorce. But statistics? It was my Mount Everest, despite help from YouTube videos on SPSS, the statistical analysis software we used (who are these people who make statistics videos for fun, anyway?).

"I’d survived childhood bullies and peer pressure, college, grad school, marriage, childrearing, a robust professional life, and even divorce. But statistics? It was my Mount Everest."

Sherrie Page Guyer, DNP student

One day, during class, I’d bravely raised my hand, but, though my professor was excellent, got no further. As I gathered up my assortment of spirals after class, a fellow student plopped a note—old school, folded tightly, handwritten—with her name and number scrawled inside, the same student who before had identified me as the “spiral-bound notetaker.”

“Call me anytime,” she said as she headed out the door to her job at a CVS Minute Clinic. “We used SPSS in my old job. I’m happy to help!” The gesture of kindness was exactly what I needed to find my bearings.

Anything new is stressful. And that applies to all nurses, whether they’re starting a BSN program or becoming certified in critical care. But we nurses can never stop learning because nursing never stops teaching.

I’ve come to embrace my DNP program’s executive format because it allows me to learn from an amazing cohort of nurses with varied backgrounds who specialize in everything from primary and acute care to business, academics, and military nursing. Though we spend more time together online than in person, I’ve learned so much from my classmates and colleagues. Still, I never miss our monthly in-person courses. There’s magic in being together.

"Sure, we scatter after class: there are night shifts to work and kids to pick up from school and longer trips home than the 75 miles I drive each way. But I'm content. Sometimes I even splurge on a hotel room so I can spend the next day immersed in the quiet library—an old friend welcoming me back as I slowly master new ways of learning."

-

Sure, we scatter after class: there are night shifts to work and kids to pick up from school and longer trips home than the 75 miles I drive each way. But I'm content. Sometimes I even splurge on a hotel room so I can spend the next day immersed in the quiet library—an old friend welcoming me back as I slowly master new ways of learning.

And who knows? Maybe soon I’ll dig out that nurse practitioner's number and see if she’d like to get coffee sometime.

DNP student Sherrie Page Guyer is an advanced practice nurse who lives in Richmond. A former school nurse and current freelance writer, she hopes to address the teen mental health crisis and bring awareness to nursing issues by publishing in the lay press and professional literature. On track to graduate from UVA in spring 2025, she’s published in Newsweek, Inside Higher Ed, Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, Journal of Pediatric Healthcare, and Richmond Family Magazine (among others), where a version of this essay was originally printed.

Guyer would like to give a special shout-out to fellow DNP student, Mary Gerardo, the nurse practitioner whose offer to help with SPSS meant so much more.