Epidemics, Disability, and Nursing

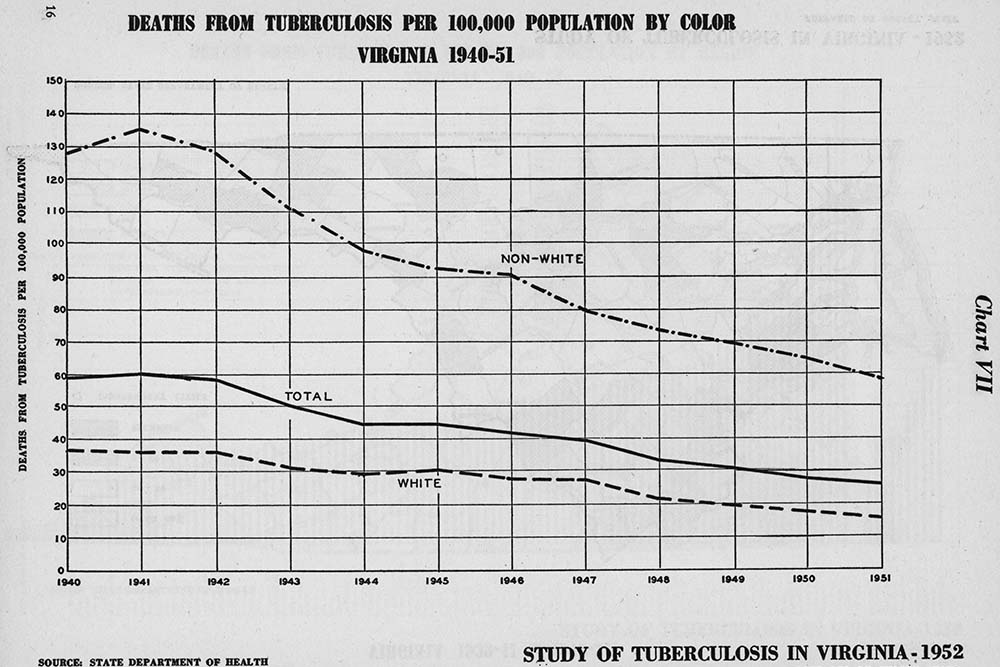

Epidemic diseases have long been a major cause of disability.

Disability was viewed as a condition to be treated and “fixed” by health professionals—not as conditions to accommodate. The goal of medical intervention was to rehabilitate and reintegrate people with disabilities into society and to, in the process, make disability (and those with them) invisible.

-

A new exhibit at the Bjoring Center examines the changing definition of disability and the role nurses played in caring for people living with disability as two major epidemics swept through the late 19th and early 20th centuries: tuberculosis and polio.

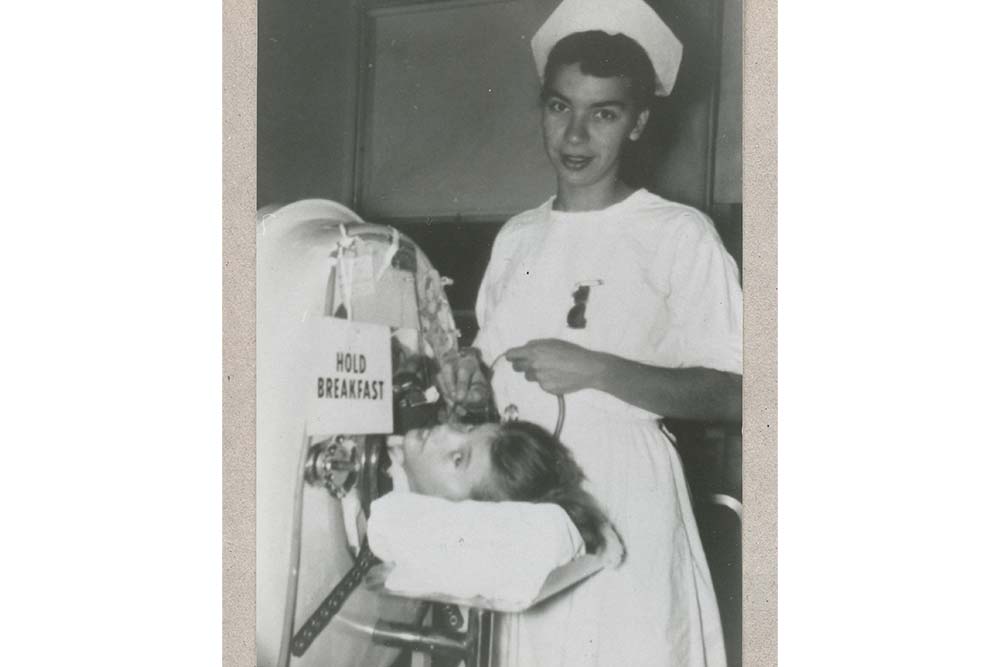

At this time, disability was viewed as a condition to be treated and “fixed” by health professionals—not as conditions to accommodate. The goal of medical intervention was to rehabilitate and reintegrate people with disabilities into society and to, in the process, make disability (and those with them) invisible. In this context, nurses were expected to support patients’ aggressive pursuit of treatments and cures even as they provided care and comfort, too. The imperative to “cure” disability, however, was infused with cultural assumptions about ability, productivity, and the worthiness of those living with disabilities.

It also caused psychological harm to patients. As clinicians pushed patients hard to overcome their disability, patients often reported feeling guilt and shame when they failed to do so.

In the 1960s and 70s, disability rights activists, many of them polio survivors, forged the disability rights movement. Rather than seeing disability as pathology, disability rights activists called for local, state, and federal initiatives to dismantle the physical barriers, prejudices, and stigma faced by people with disabilities. In rejecting this medical model of disability, these advocates also challenged what it meant to be an “expert,” asserting that people with disabilities—and not physicians, rehabilitation specialists, or other so-called experts—were, in fact, the true experts of what it meant to live with disability.

This history challenges us to consider how the social definitions and cultural meanings we ascribe to disability influence people’s experiences of it and remind us of the important roles that nurses and other health professionals play in supporting those impacted by epidemic disease.

Dominique Tobbell, author of Pills, Power, and Policy: The Struggle for Drug Reform in Cold War America, and Dr. Nurse: Science, Politics, and the Transformation of American Nursing, is director of the Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry and the 2023 recipient of an American Association for the History of Nursing H31 grant to study the evolution of nurse-led community health clinics from the 1960s to 2010. Tobbell is also writing a retrospective to mark the School’s 125th anniversary in 2025.