The First COVID Patient

When the first COVID-19 patient was brought into Cate Rhangos’ unit at Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital

on the Upper East Side of Manhattan March 13, it was like an alien spaceship had landed.

Just before midnight, six nurses shrouded in full protective gear wheeled in the middle-aged man who lay on a stretcher entirely tented in plastic. Everyone stood back. In his room, they peeled back the layers and helped him to bed. The man was alert, could walk, talk and stand on his own. Other than a fever, a ragged cough, and runny nose, “he was human,” recalled Rhangos (BSN `19), who’s originally from Savannah, Ga. “It wasn’t like this crazy thing that we’d all been preparing for since the beginning of the pandemic; he seemed OK.”

“I told him I was Cate, and that I’d be taking care of him, and he looked at me like, ‘Am I going to die here?’”

Cate Rhangos, ICU nurse who cared for Sloan-Kettering's first COVID patient last month

Rhangos’ encounter with Sloan Kettering’s first COVID patient occurred just as coronavirus swept through New York City, and cases there began their meteoric rise. It was a moment before many states, including Virginia, had issued stay-at-home orders, before public schools had shuttered across the country, even before UVA cancelled its 2020 graduation and urged students on spring break not to return to Grounds. COVID-19, which had ravaged Europe and Asia before it, was largely still a mystery.

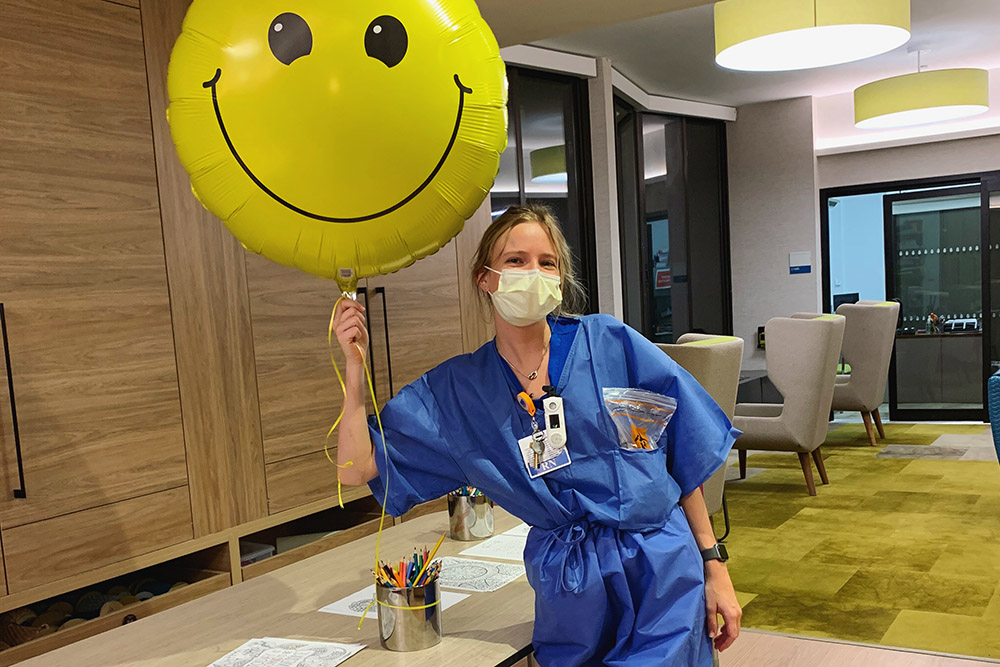

The hospital, however, had been preparing for weeks, changing protocols and migrating patients in anticipation of the coming onslaught. Visitors were banned. Hospital staff were required to wear face masks, though it would be another three weeks before nurses caring for COVID patients would don mint green surgical scrubs covered by protective paper pantsuits (“only available in extra-large,” said Rhangos) that they changed into at the hospital once they’d begun their shift.

That first night, though, the man didn’t get much sleep, and respectfully tried not to cough when Rhangos entered the room to talk, offer water, take his vital signs, or adjust his bedding. The in-room TV blared only news about coronavirus, and New York City as the nation’s disease epicenter. When they talked, he asked Rhangos questions she couldn’t answer. “The craziest thing about it,” she recalled, now nearly a month later, was “his concern for everybody else he’d encountered. He kept asking, ‘How long have I been contagious? What are the chances I infected others? Who do I need to call? And will everyone be taken care of?’”

The following morning early, Rhangos, who’d eaten a somber lunch with coworkers around 2 a.m., asked if she could help him wash up. Warm water, soap, some toothpaste, and a shave—"Just for some sense of normalcy,” she explained to him, as much to him as to herself. They chatted about his family, his concerns for his wife, who he felt should get tested. A normal, basic nurse-patient interaction, until you considered the world raging outside. Here, on the fourth floor of Sloan Kettering, they formed an easy alliance.

One of the nurses on duty that night would be chosen to care for him, the shift manager had said, who’d written names on tiny slips of paper and found a hat. Rhangos, who’d worked in the Manhattan hospital for just eight months caring for patients with cancer who were recovering from neuro- or orthopedic surgeries, spoke up.

“I just decided right then and there,” she said, of her decision to volunteer. “No need to do the hat.”

And so Rhangos, wearing a mask over her nose and mouth, introduced herself to the man with coronavirus in the same way she would to any other patient on any other night.

“I told him I was Cate, and that I’d be taking care of him,” she recalled, “and he looked at me like, ‘Am I going to die here?’”

“When I’m in the room, it feels very normal,” said Rhangos, who has in her shifts since cared for dozens of other COVID patients who now occupy all five floors of Sloan Kettering. “I‘m doing all the same things I’ve been doing for months. But when I leave the room, and take off my [personal protective equipment] PPE, and I take a big breath” the gravity hits her.

Rhangos’ first COVID patient—released home just a week later—was a success story, unlike many of those patients she cared for in the weeks after, who arrived sicker, more desperate, and in greater numbers. Currently, Rhangos said, the hospital is caring for more than 100 COVID patients, and her entire unit, all 37 rooms, is brimming with people suffering in varying degrees from coronavirus.

She finds comfort in her coworkers, speaking with her parents, especially her mom, a fellow nurse. She’s trying to sleep and take walks along the East River on nearly deserted sidewalks. She’s experimented with cooking, too—homemade pizza, pasta, and salad dishes, mostly, though donations of food to the hospital have been abundant. She is struck by the strangeness and familiarity of her work, even on the now-empty streets of New York City.

“You’re still a nurse and [COVID] doesn’t change the way you care,” she said. “We have to remember to treat them like people, like human beings. That’s easy to forego in a time of crisis like this—but that’s the most important and fundamental purpose of nursing.”

And were she to see that first patient again, after all this is over—maybe on the bus, in an Uber, or on a bustling sidewalk, she’d know him. She’d smile, say hello, and maybe shake his hand, or offer a hug.

“It would make my week, seeing him again,” she said. “We both had a big impact on each other’s lives and seeing him happy and healthy and with his family—well, that’s why we do it.”