RNs' Rx: Quarantine, Fresh Air and Sunlight

When coronavirus hit, UVA was one of many institutions to quickly take action earlier this spring

to reduce the virus’ spread by encouraging students to remain home, cancelling gatherings, and moving university courses online for the foreseeable future. Such measures indicate the seriousness of the current outbreak and the desire to reduce concurrent infections of COVID-19, which has been declared a pandemic and remains dramatically more deadly than influenza.

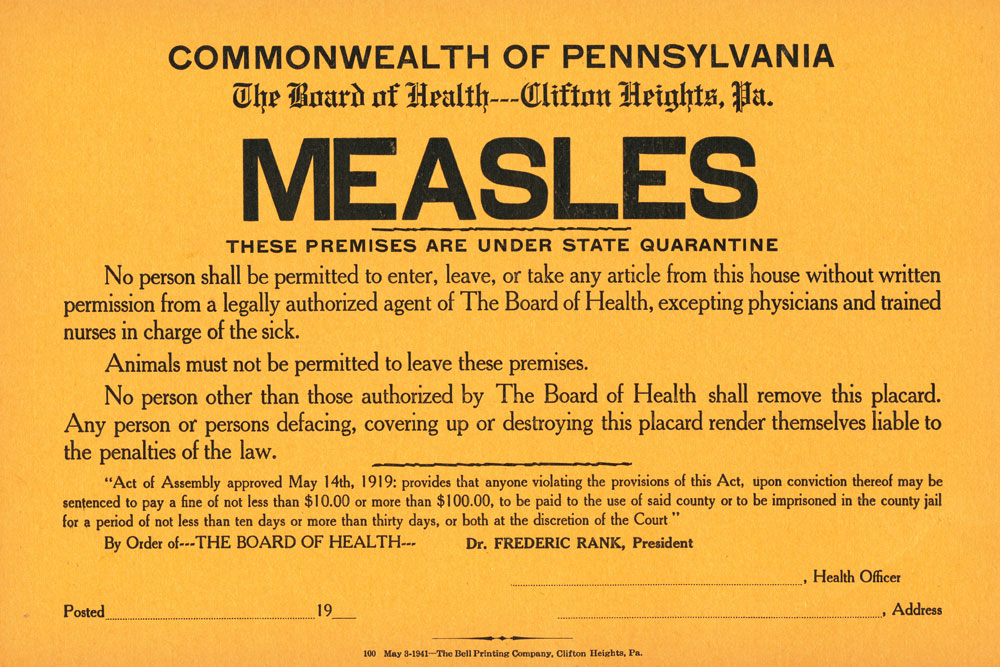

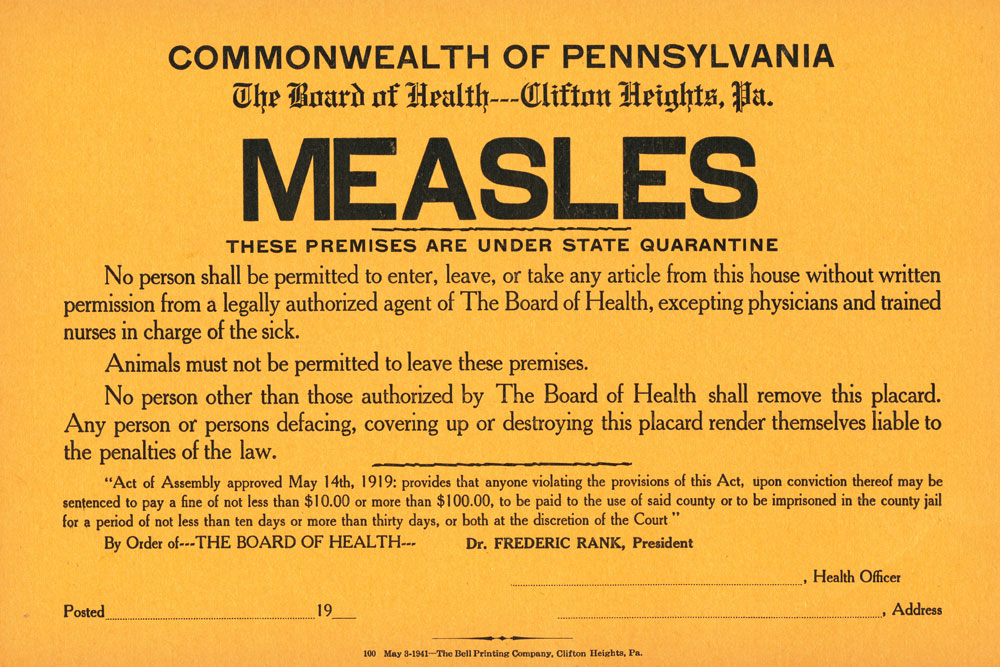

But even as COVID-19’s impact intensifies, affecting each of us personally and making many feel as though we’re moored in uncharted waters, it should be noted that the concepts of social distancing and quarantine are not new--and they really work!

Quarantine as a practice began in the 1300s to protect European coastal cities from the plague. Ships arriving into Venice, for example, were required to anchor off coast for 40 days before being allowed to port, a practice that birthed the word quarantine (in Italian, quaranta giorni), which literally means 40 days.

In the early days of the United States, however, little was done to restrict the spread of disease to our new nation’s ports because such rules fell under local and state jurisdiction. That meant regular outbreaks of yellow fever and, later, cholera, until Congress passed national quarantine legislation in 1878 that, according to the CDC, “paved the way for federal involvement in quarantine activities.”

Quarantine had become formalized. Federally-employed U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) officers wore uniforms while performing their official quarantine duties, though the PHS as a department leapfrogged from entity to entity: first, it was part of the Treasury, then part of the Federal Security Agency, then the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and today, it’s part of the Centers for Disease Control.

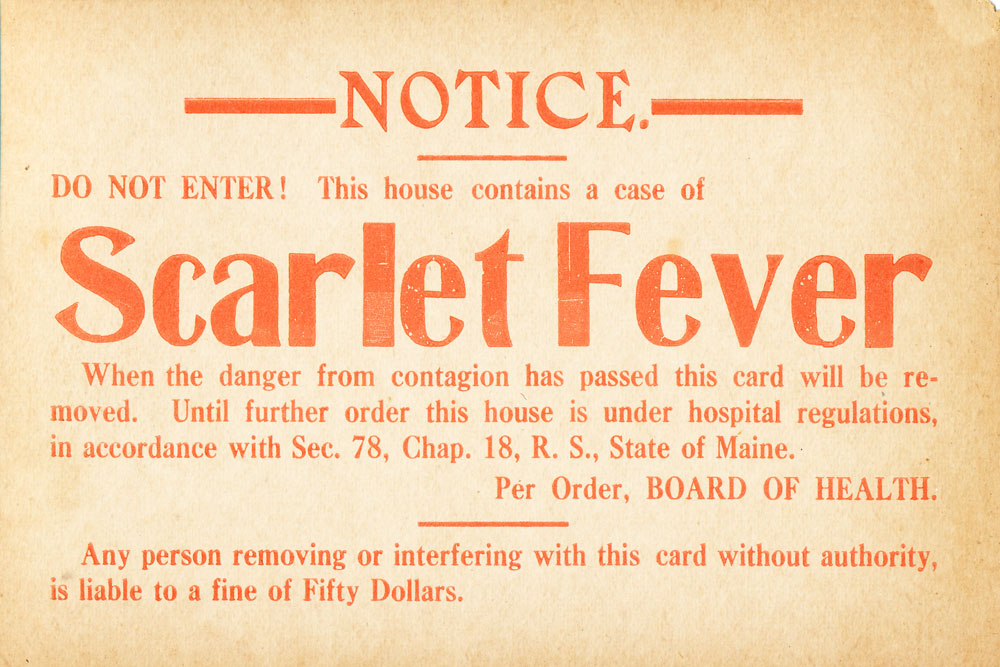

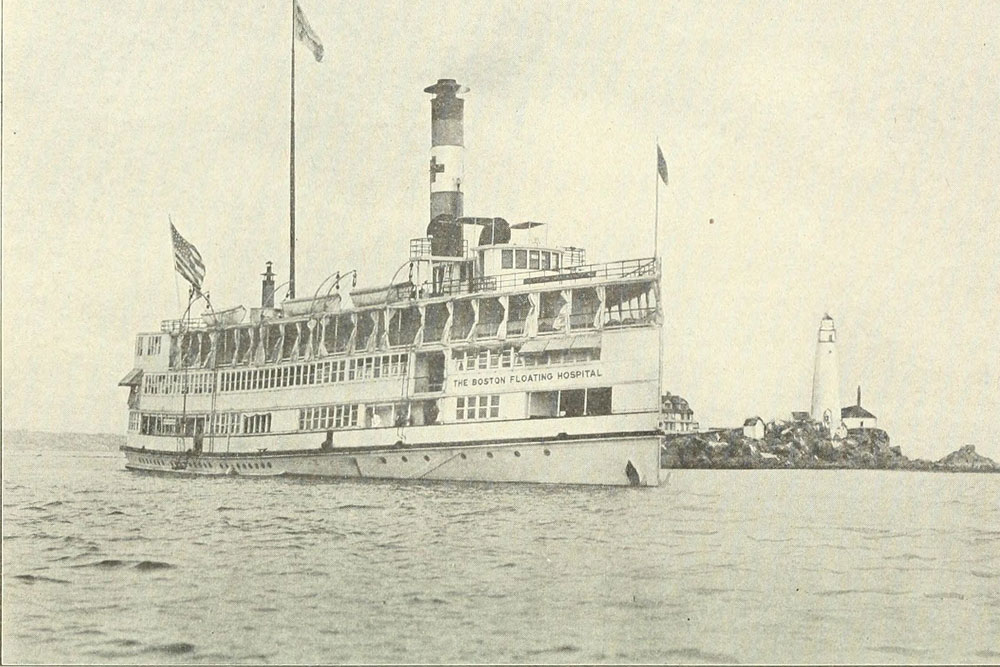

Then, as now, nurses have always been caregivers on the frontlines of quarantines, and did what they could to ensure the health and wellbeing of isolated patients. Fresh air and sunshine have long been considered therapeutic since Florence Nightingale recommended well-ventilated pavilion hospitals in the 1860s. By the late 1880s, visiting nurses in New York City and Boston organized day-long excursions for ill children aboard the steamboat Emma Abbot and the Boston Floating Hospital so they could experience “healthy sea breezes.” By the early 20th century, nurse Lillian Wald erected playgrounds and established summer camps for immigrant children living on the Lower East Side to promote wellness, while Philadelphia nurses staffed open-air hospitals for ill babies on the Schuylkill riverfront (Annals of the American Academy of Political Social Science, 1911).

Seaside trips were part of the regimen recommended to prevent kids from getting tuberculosis or aiding in their recovery (recall the tragedy and triumph of the children’s classic book THE VELVETEEN RABBIT), and many nurses were staunch advocates of heliotherapy – the therapeutic use of sunlight – throughout even the most frigid months in both Europe and the U.S., including these UVA Hospital nurses who took their young patients to the hospital rooftop about 1925. Swiss physician Auguste Rollier exposed his young patients with TB to hearty doses of direct sunlight, even in the chilly northern climates of Switzerland, to “heal tubercular lesions with light and Vitamin D . . . emphasizing the nurses’ physical and emotional care of children isolated from their parents during long courses of treatment” (Brodie: 2015).

Fresh air was also recommended for preventing the spread of disease. During the 1918 flu pandemic, governments mandated that church services be held outdoors, and that bus and trolley windows remain open.

And nurses have always been champions of a thorough handwashing, which remains one of the best, and most basic ways we can stay well, in addition to cough and sneeze etiquette.

From your #FlashbackFriday and Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry friends: open your windows, stay well, and know that COVID-19 precautions – while frightening to some – are based very much on solid science grounded in history.

+++

Special thanks to AAHN President Arlene Keeling, professor emerita, Barbara Brodie, professor emerita, and the book A PROFESSIONAL HISTORY OF NURSING IN THE UNITED STATES (2019); Connelly’s SAVING SICKLY CHILDREN: THE TUBURCULOSIS PREVENTORIUM IN AMERICAN LIFE (2008); Brodie’s CHILDREN OF THE SUN, from 2015 Windows in Time. Photos courtesy of the Bjoring Center Archives, the Centers for Disease Control, and Tufts Floating Hospital for Children archives.