Managing, Shift by Shift

None of us know if we are positive for the coronavirus.

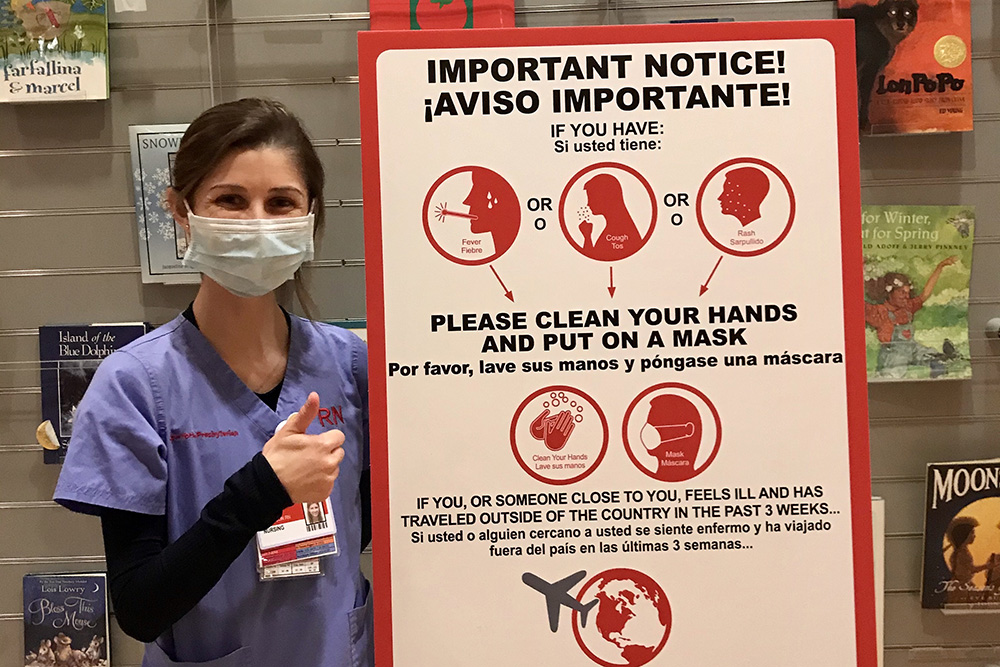

Lauren Dickinson (BSN `19) and her colleagues at New York-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital live with this anxiety as they care for patients at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We constantly wonder and question who is positive,” Dickinson says. “Did we give the virus to our patients, or did they give it to us? We talk about it a lot. It’s very hard.”

During the first week of April, as New York City struggled to respond to the surge of coronavirus patients, each day brought a new and different reality: changing protocols, growing shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), mounting fear coupled with mounting fatigue. The previous week, the hospital had begun the controversial practice of “ventilator sharing”—reconfiguring a device intended for one patient to be used for multiple patients—in a desperate bid to address the dearth of critical breathing machines.

“There is no benefit to thinking about what could happen. You just walk in as a healthcare provider and know you are there to provide compassionate, whole-hearted care. I try to keep that at the forefront.”

ICU nurse Lauren Dickinson (BSN `19), who's caring for COVID patients at NY Presbyterian Children's Hospital

Dickinson dons one mask just for the 30-minute subway ride from her apartment in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District to the hospital’s Columbia campus, on the Upper West Side of this city of 8.3 million. At the start of her night shift, she signs out a new surgical mask and is encouraged to wear it throughout her shift, unless it’s visibly soiled, since there remains an overall shortage. Reusing masks that, prior to the outbreak, were thrown away after each use, heightens the unease, but there is lift in seeing the multicolored donated homemade masks that many nurses now wear. If she goes into an infected room, she uses yet another different mask and must be careful to put it back on whenever she re-enters that particular room.

Dickinson sees nurses from the COVID-19 floors coming off their shifts as she begins hers. They are exhausted and wear a demeanor unfamiliar to Dickinson. They have already seen many patients die.

Dickinson has been a nurse for less than a year. Normally, her young patients are among the hospital’s most vulnerable: those on the hematology-oncology unit, currently designated a “clean” floor (without any COVID-19 patients). But when the hospital puts out a call in early April for volunteers to staff the adult COVID-19 units, Dickinson steps up. She is outfitted with a N95 mask, eye goggles, a hair net, and shoe covers that reach her knees.

Her first shift caring for COVID-19 patients leaves Dickinson depleted, and gives her a sobering vantage inside the world of coronavirus and a view of the strength and compassion of her patients and colleagues.

“The patients are extremely sick and scared,” she says. “They fear the turn their health may take with this virus and they have to battle it all alone, as no visitors are allowed at the bedside.”

Still, Dickinson feels prepared. Nurses, after all, are trained to accept risk.

“UVA trained us to approach the situation at hand with confidence that we are capable of handling the current crisis,” says Dickinson. “There is no benefit to thinking about what could happen. You just walk in as a healthcare provider and know you are there to provide compassionate, whole-hearted care. I try to keep that at the forefront.”

In the middle of the night when they take a break, she and her fellow nurses talk about their fears and share what they are grateful for. Then, they force themselves to change the subject.

They share photos, laugh—anything to let off steam. At home after her shifts, Dickinson connects with her family in Richmond, Va., over FaceTime, sharing dinner and conversation remotely.

“I truly believe we will all come out stronger nurses and stronger people at the end of this. At this point,” she says, “we truly can only take life day by day.”